How do director, designers and actors prepare to realize John Webster’s Jacobean blockbuster, The Duchess of Malfi, for a modern audience? What challenges do the artists face along the way? How does their vision evolve over the course of rehearsal?

This is the first in a series of articles documenting the upcoming production at Writers' Theatre in Glencoe, adapted and directed by Artistic Director Michael Halberstam. This part addresses the problems posed by a text that's almost 400 years old.

Part I: John and Michael

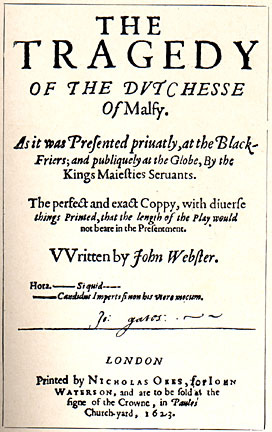

John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi was produced for the first time in 1614. That was a long time ago. Webster’s audience wore doublets and farthingales, danced the galliard, read Pliny’s Natural History (or pretended at parties that they had), attended public hangings, cheered and dreaded a king, and died of the plague or the clap more often than of old age.

So how -- and why -- do you stage The Duchess of Malfi today? In a speech welcoming his assembled cast at their first read-through, director and adaptor Michael Halberstam offers his answers.

The “why” is easy: “It’s a bloody good play,” Halberstam tells them. “It’s one of a number of wonderful plays by contemporaries of Shakespeare that have simply been eclipsed by his brilliance.”

And Halberstam believes that Jacobean drama may have a special resonance today. “Jacobean England was in the twilight of an empire, the same family had been in power for decades, wealth was power and was concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer individuals, corruption was rampant, and the populace was fat, comfortable and drawn to lurid entertainments.” Tax cuts for the rich, Enron, Hostel -- all reasons we might have an affinity for Jacobean drama.

But a lot still stands between modern audiences and Webster’s text. The story of the Duchess of Malfi was well known in Webster’s time, so he could leap over plot points. Topical references that were instantly recognizable to Jacobean audiences leave modern audiences perplexed. And Jacobean English sometimes sounds like a foreign language.

These are the problems that Halberstam hopes to solve with his adaptation of the play. As he tells his cast with a certain glee, “Webster is dead, the play is in the public domain, and we can do whatever we want!”

At first blush, that’s a startling declaration from the Artistic Director of a company known for its devotion to the text. As Halberstam explains it, though, his intent is not to substitute his vision for Webster’s but to realize Webster’s vision in terms that a modern audience can access. He means to create a modern equivalent to the experience that Webster’s audience would have had sitting on wooden benches in the Blackfriars theatre in 1614, listening to a new treatment of a well-known story full of slang and sly references to the politics of the day.

With that aim, Halberstam has pruned the text of arcane and archaic references like, “Their livers are more spotted than Laban’s sheep.” He has added a prologue to fill in some of the background that the Jacobeans had at their fingertips. And where Webster counted on his audience to fill in gaps in the familiar tale, Halberstam has inserted masques -- sequences of mime and dance -- to carry the plot forward.

Will it work? These are early days yet. Four weeks of rehearsal lie ahead. The actors must master language that is still far removed from contemporary speech and learn to inhabit characters whose assumptions and motivations are sometimes distant from our own. Costumes, set, sound and lighting design, dance and fight choreography are all works-in-progress.

During the read-through, Halberstam is scribbling in his script. It appears that even the adaptation is still a work in progress.

Anne Nicholson Weber |

|

| Theatre In Chicago News Contributor Anne Nicholson Weber saw "Jack and the Beanstalk" at the Goodman Children's Theater and has loved the theatre ever since. She is a Chicago writer and the author of Upstaged: Making Theatre in the Media Age | |

Follow Us On Twitter

Follow Us On Twitter