Though the tradition dates from antiquity, for modern audiences, it all started in 1980 with the Royal Shakespeare Company's eight-and-a-half-hour Nicholas Nickleby, a sprawling adaptation of the Charles Dickens novel that launched a fashion for marathon productions of duration sufficient to require at least one extended intermission for playgoers to fortify themselves with nutrition more substantial than lobby snacks. In order to prevent customers straying too far on their foraging expeditions, theaters began to offer in-house provender—an amenity rendering menu selection an important element for undertakings like The Hypocrites' current staging of Sean Graney's All Our Tragic, inaugurating the multiple-story Den theater's new first floor storefront auditorium.

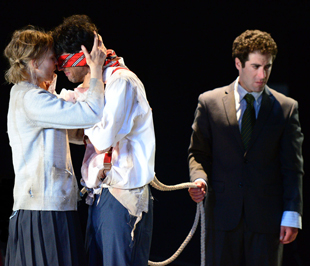

Fortunately, The Hypocrites are experienced at feeding customers, their aesthetic encompassing nosherie and libations designed to create a relaxed atmosphere for innovative interpretations of classic repertoire—e.g. a beach-resort Pirates of Penzance, or a rec-room Romeo and Juliet. This latest experiment proposes a comprehensive survey of all thirty-two extant Greek tragedies compressed into nine hours of playing time, augmented by three hours of intermissions, including breaks for meals.

"The full-day performances are replicated on the Dionysic festivals in ancient Athens," Megan Wildebour explains, "Citizens would meet there for a festival of entertainment, but also for swapping news with their neighbors—especially the civic issues brought into focus by the plays they had just all seen together. Our goal is to create that kind of community, with strangers bonding in a shared space over the course of the day."

The most recent attempt at this kind of "dinner theater" was Chicago Shakespeare's 2004 "Rose Rage" Henry VI , featuring actors dressed as butchers, whaling with cleavers on piles of animal innards. Box suppers were provided for patrons at that event—although it was rumored that the roast beef entrees were rejected by diners temporarily unnerved by the sight of red meat.

Wildebour chuckles, "When we did Sophocles: Seven Sicknesses, we looked for what would please a variety of palates, and since The Hypocrites try to avoid any animal products onstage or off, we leaned toward vegetarian. Sean was fond of Sultan's Market, so it became the logical choice. We also think boxed meals are cheap and depressing, so instead, we are setting up three serving stations stocked at all times with grab-and-gobble treats."

The Den was once a mixed-use commercial and residential building—does it have a kitchen hidden away somewhere? "They have a full-service cash bar for drinks and a bottomless-cup-of-coffee special on the long days. We don't prepare any food on-site, but we have a big refrigerator, so whatever our overworked and underpaid artists don't take home can be stored for the next day."

Artists usually don't hire on as cooks or waiters, and most theater rosters don't list a "mess sergeant" or "refreshment designer" on their staff, leaving Wildebour, in her capacity as Managing Director, in command of the culinary logistics. Fortunately this year, she doesn't have to do it all by herself.

"We call them the 'army of interns'," she reports gleefully, speaking of the seven front-of-house assistants who completed a crash course in food service and Greek Theater History as preparation for their duties as guides to the food, the facility and the play. "You can ask them questions about anything from the ingredients in the sandwiches to how Melpomene became the designated muse of tragedy."

All Our Tragic runs at The Den through October 5.

Mary Shen Barnidge

Contributing Writer

Follow Us On Twitter

Follow Us On Twitter