When death was more public and playhouses bigger, plays frequently featured sensational spectacle difficult to reproduce in modern theaters, where the level of realism achieved in cinema has raised the bar on audience expectations. The biggest obstacle to performing Oscar Wilde's Salomé in 2011 is not its Biblical origins, its lyrical language, or even its leading lady's erotic dance, but the graphic decapitation of Iokanaan (the fictional counterpart of John The Baptist) that figures in the play's grisly climax. Not only does the script mandate that this gruesome object resemble the actor playing the martyred saint, but that it be fondled by the actress portraying the temptress responsible for its owner's execution.

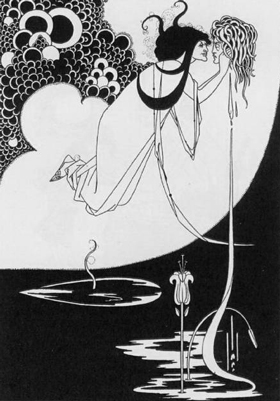

Suspension of disbelief decreases in quick proportion to audience proximity, increasing the challenge to National Pastime Theater in preventing playgoers seated within its intimate storefront space venting their nervousness in derisive giggles and groans. Arriving at a solution called for the collaborative efforts of property designer Phillip Denofrio, costume and makeup designer Julia Zayas-Melendez, and fight designers Richard Gilbert and David Gregory, all drawing their collective inspiration from the famous Aubrey Beardsley illustration.

Ironically, the show's violence consultants deny significant influence on the creation of the gory appendage. "All we contributed was some discussion about wrapping a cloth around the base of the skull and not using wet blood," insists Gilbert, "All the credit goes to Phil and Julia."

Denofrio first sculpted the head on a pre-existing mannequin before brushing on plaster, layer by layer, until both the weight and size seemed appropriate. After drying and sanding, the head was painted a skin tone slightly paler than the living Iokanaan's complexion. It was then ready for "dressing."

Using photos of actor Joshua Harris, Zayas-Melendez cut and styled a wig to the shape of his hairline, making Iokanaan's beard from the cuttings. Once the hair was firmly attached, she painted on the eyes and lips. "At first preview, it looked surprisingly realistic—held up full-front, the face was clearly a face," she recalls, "but the bloody fabric I'd chosen for the base wasn't quite right, so it went back to Phil."

"The Beardsley picture shows blood flowing from the neck," Denofrio explains, "so I dirtied up the wrapping-cloth a bit and added the red silk 'ribbons' trailing from the neck when it's picked up, along with a lacquer spray to give it a sweaty appearance."

The final illusion, however, was in the manner of the dismembered head's presentation. The repulsive trophy is brought in from upstage, where it remains for the duration of the scene, the actors initially directing our attention to it for a fleeting moment of horror, before turning away and moving downstage to draw our eyes away from protracted scrutiny of a sight hitherto existing only in our imaginations.

Salomé runs through August 20, headlining National Pastime Theater's annual Naked July: Art Stripped Down festival.

Mary Shen Barnidge

Contributing Writer

Follow Us On Twitter

Follow Us On Twitter