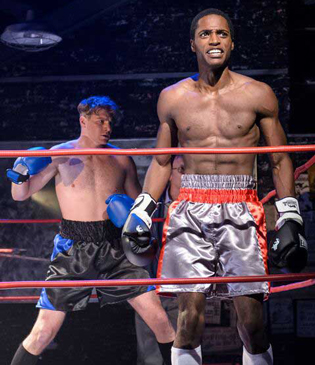

Despite the conspicuous presence of athletes wearing padded gloves and silk trunks, Roy Williams' Sucker Punch is a play about fighting, and not just boxing. When the slum-dwelling citizens seeking refuge from poverty and violence in Charlie Maggs' shabby gymnasium aren't mixing it up in the ring, they're practicing in anticipation of achieving their moment of glory, and when they're not practicing, they're rough-housing with each other—sometimes playfully, sometimes not. In this angry world, men who years earlier abandoned their hopes for a championship retain their scrappy defiance, and teenage girls in private-school uniforms smack the speed-bag in moments of frustration.

It takes two designers—fight choreographer Chuck Coyl and boxing coach Ruben Gonzalez—to create a physical language acknowledging the formal vocabulary of boxing according to tournament rules, while still conveying the swiftly-changing dynamics of perpetrators accustomed to street brawling. Fortunately, Victory Gardens director Dexter Bullard has long understood the importance of body language as an integral part of acting. Too many cooks in the kitchen can end up stumbling over each other's feet, however, making clear division of labor essential when instructing seven cast members in the "sweet science."

"Beginning seven weeks before we opened, Ruben started turning the fighting actors—Leon and Troy and Tommy—into boxing actors, training in the rehearsal room, outside in the parks and even in his own basement." Bullard explains, "In addition to breathing, rhythm and conditioning—getting used to holding up their extended arms for long stretches of time, for example—they learned the elements of punches, evasions, heavy-bag and speed-bag techniques, as well how to shadow-box to quicken their response times, jump rope to develop flexibility in their legs, and wrap their hands in tape to keep their wrists rigid before putting on the gloves."

The attention to breath control pays off in the scene where Leon delivers a five-minute monologue while simultaneously cross-jumping rope—all without ever running short of lung power. Coyl's movement for the actors of—ahem!—advanced years didn't permit them to sit out the workout sessions, either. Bullard reports John Judd, playing the gruff Charlie, devoting long hours to learning practice-mitts drill, and Kenn E. Head ("who's in terrific shape, by the way") reviewing safe ways to fall down after Leon, at one point, gives his father a shove to send him sprawling to the floor.

Nothing thrills audiences like fisticuffs, though. After familiarizing us with the sound of leather-striking-leather during the opening sequence with Charlie and Tommy exercising with the padded mitts, and making us aware of the volatile racial tensions underlying the most innocuous of conversational exchanges, the fighters need only to swing and recoil—occasionally connecting with each other's gloves to elicit a "knap" or two—and we flinch, so sensitized have we become to expectations of violence.

From Prop Thtr's Never Come Morning in 1995 to Red Orchid's The Opponent in 2012, literally every boxing play produced in Chicago has been a massive hit with audiences. Can it be true that theater audiences—as the cynical Squid remarks—"love to see men beat up on each other, because they're afraid to do it themselves"? Bullard argues that blood sport and theater have always been closely related.

"Wasn't the Globe modeled on bear-baiting pits? Didn't the Romans take the old Greek plays and restage them with the bloodshed in full view? Boxing is intimate, like scene work. It's physical, it's sensational, it's measured in rounds—or 'acts', as we call them—and its entertainment value lies in its emotional highs and lows. Isn't this what we look for in a play?"

Sucker Punch runs at Victory Gardens through October 18.

Mary Shen Barnidge

Contributing Writer

Follow Us On Twitter

Follow Us On Twitter